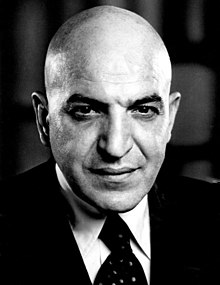

Telly Savalas

Telly Savalas | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Savalas in 1973 | |||||||||||||||

| Born | Aristotelis Savalas January 21, 1922 Garden City, New York, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Died | January 22, 1994 (aged 72) | ||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, California, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Occupation(s) | Actor, singer | ||||||||||||||

| Years active | 1950–1994 | ||||||||||||||

| Spouses | Katherine Nicolaides

(m. 1948; div. 1957)Marilyn Gardner

(m. 1960; div. 1974)Julie Hovland

(m. 1984) | ||||||||||||||

| Children | 6, including Ariana Savalas | ||||||||||||||

| Military career | |||||||||||||||

| Service | United States Army | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Website | tellysavalas | ||||||||||||||

Aristotelis "Telly" Savalas (January 21, 1922 – January 22, 1994) was a Greek-American actor. Noted for his bald head and deep, resonant voice,[1][2][3][4] he is perhaps best known for portraying Lt. Theo Kojak on the crime drama series Kojak (1973–1978) and James Bond archvillain Ernst Stavro Blofeld, in the film On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969).

Savalas' other films include: Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), Battle of the Bulge (1965), The Dirty Dozen (1967), Kelly's Heroes (1970), Horror Express (1972), Lisa and the Devil (1974), and Escape to Athena (1979). For Birdman of Alcatraz, he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor and the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor.

In music, Savalas released a cover of the Bread song "If", which became a UK number-one single in 1975.[5]

Early life

[edit]Aristotelis Savalas (Greek: Αριστοτέλης Σαβάλας)[6] was born in Garden City, New York, on January 21, 1922, the second of five children born to Greek parents Christina (née Kapsalis), an artist who was a native of Sparta, and Nick Savalas, a restaurant owner. His paternal grandparents came from Ierakas. Savalas and his brother, Gus, sold newspapers and polished shoes to help support the family.[7] Savalas initially spoke only Greek when he entered grade school, but later learned English. He attended Cobbett Junior High School in Lynn, Massachusetts. He won a spelling bee there in 1934; due to an oversight, he did not receive his prize until 1991, when the school principal and the Boston Herald awarded it to him.[8]

Savalas graduated from Sewanhaka High School in Floral Park, New York, in 1940.[9] A renowned swimmer, he worked as a beach lifeguard after graduation from high school. On one occasion, though, he was unsuccessful in saving a father from drowning; as he attempted resuscitation, the man's two children stood nearby crying for their father to wake up. This affected Savalas so much that he spent the rest of his life promoting water safety, and later made all six of his children take swimming lessons.[10]

Military service

[edit]In 1941, Savalas was drafted into the United States Army. From 1941 to 1943, Savalas served in Company C, 12th Medical Training Battalion, 4th Medical Training Regiment at Camp Pickett, Virginia. In 1943, he was discharged from the Army with the rank of corporal after being severely injured in a car accident. Savalas spent more than a year recuperating in hospital with a broken pelvis, sprained ankle, and concussion.[11] He then attended the Armed Forces Institute, where he studied radio and television production.[12]

He received a bachelor's degree in psychology from Columbia's School of General Studies in 1946[6][13] and started working on a master's degree while preparing for medical school.[14]

Career

[edit]Early roles

[edit]After the war, he worked for the U.S. State Department as host of the Your Voice of America series, then at ABC News.[15][16] In 1950, Savalas hosted a radio show called The Coffeehouse in New York City.[17]

Savalas began as an executive director and then as senior director of the news special events at ABC. He then became an executive producer for the Gillette Cavalcade of Sports, where he gave Howard Cosell his first job in television.[17][18] Before his acting career took off, Savalas directed Scott Vincent and Howard Cosell in Report to New York, WABC-TV's first regularly scheduled news program in fall 1959.[citation needed]

Savalas did not consider acting as a career until asked if he could recommend an actor who could do a European accent. He did, but as the friend in question could not go, Savalas himself went to cover for his friend and ended up being cast on "And Bring Home a Baby", an episode of Armstrong Circle Theatre in January 1958. He appeared on two more episodes of the series in 1959 and 1960, one, acting alongside a young Sydney Pollack.[19] He was also in a version of The Iceman Cometh.[20]

He quickly became much in demand as a guest star on TV shows, appearing in Sunday Showcase, Diagnosis: Unknown, Dow Hour of Great Mysteries (an adaptation of The Cat and the Canary), Naked City (alongside Claude Rains), The Witness (playing Lucky Luciano in one episode and Al Capone in another), The United States Steel Hour, and The Aquanauts.[21][22] He was a regular on the short-lived NBC series Acapulco (1961) with Ralph Taeger and James Coburn.

Savalas made his film debut in Mad Dog Coll (1961), playing a cop.[23] His work had impressed fellow actor Burt Lancaster, who arranged for Savalas to be cast in the John Frankenheimer-directed The Young Savages (also 1961 and again playing a cop).[23][6] Pollack worked on the film as an acting coach.[24]

In one of his most acclaimed performances, Savalas reunited with Lancaster and Frankenheimer for Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), where he was nominated for the Academy Award and Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor. The same year, he appeared as a private detective in Cape Fear (directed by J. Lee Thompson with whom Savalas would work in future films), and The Interns, reprising his role from the latter film in The New Interns (1964).[25]

Savalas also guest-starred in a number of TV series during the decade including The New Breed, The Detectives, Ben Casey, The Twilight Zone (the episode "Living Doll"),[23] The Fugitive, and Arrest and Trial among others.

Baldness and stardom

[edit]

He continued in supporting roles in films such as The Man from the Diners' Club, Love Is a Ball, and Johnny Cool (all 1963).[23][26] Already at a late stage of male pattern baldness, he shaved his head to play Pontius Pilate in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)[23] and kept his head shaven for the rest of his life.[27] He reunited with J. Lee Thompson in John Goldfarb, Please Come Home! (1965), and was one of many names in Genghis Khan (also 1965).[6]

He was part of an all-star cast in The Dirty Dozen (1967), playing Archer Maggott (the worst of the dozen), in a role Jack Palance turned down. He reunited with Burt Lancaster and Sydney Pollack in the Western The Scalphunters (1968), and also featured in the comedy Buona Sera, Mrs. Campbell (also 1968)—noted as one of his favorite roles—and the all-star action movie Mackenna's Gold (1969), his third film for J. Lee Thompson.[28] Savalas attributed his success to "his complete ability to be himself."[29]

Savalas' first leading role in film was in the British crime comedy Crooks and Coronets (1969). The same year, he appeared in the James Bond movie On Her Majesty's Secret Service, playing Ernst Stavro Blofeld. He continued to appear in films during the 1970s including Kelly's Heroes (1970) (with Clint Eastwood); Clay Pigeon (1971); and several European features such as Violent City (1970) (with Charles Bronson); A Town Called Bastard (1971); Horror Express (with Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee); A Reason to Live, a Reason to Die; the title role in Pancho Villa (all 1972); and Redneck (1973). He reunited with Christopher Lee in the 1976 thriller Killer Force, and also appeared in Peter Hyams' Capricorn One (1978).[23][30]

"I had worked my way up to star billing", he later said, "when the bottom dropped out of the movie business. I could have stayed in Europe and made Italian movies, but I discovered the big difference between an Italian and American movie is that in the American movie, you get paid."[31]

Kojak

[edit]Savalas first played Lt. Theophilus "Theo" Kojak in the TV movie The Marcus–Nelson Murders (CBS, 1973), which was based on the real-life Career Girls murder case.[32]

Kojak was a bald New York City detective with a fondness for lollipops and whose tagline was "Who loves ya, baby?" (He also liked to say, "Everybody should have a little Greek in them.") Although the lollipop gimmick was added to indulge his sweet tooth, Savalas also smoked heavily onscreen—cigarettes, cigarillos, and cigars—throughout the first season's episodes. The lollipops had apparently given him three cavities, and were part of an (unsuccessful) effort by Kojak (and Savalas himself) to curb his smoking. Critic Clive James explained the lead actor's appeal as Kojak: "Telly Savalas can make bad slang sound like good slang and good slang sound like lyric poetry. It isn't what he is, so much as the way he talks, that gets you tuning in."[33]

David Shipman later wrote: "Kojak was sympathetic to outcasts and ruthless with social predators. The show maintained a high quality to the end, mixing tension with some laughs and always anxious to tackle civic issues, one of its raisons d'etre in the first place. It was required viewing in Britain every Saturday evening for eight years. To almost everyone everywhere, Kojak means Savalas and vice versa, but to Savalas himself, the series was merely an interval, albeit a long one, in a distinguished career."[30]

Kojak aired on CBS for five seasons from October 24, 1973, until March 18, 1978, with 118 episodes produced.[23] The role won Savalas an Emmy and two Golden Globes for Best Actor in a Drama Series. Co-stars on the show included Savalas' younger brother George as Detective Stavros, a sensitive, wild-haired, quiet, comedic foil to Kojak's street-wise humor in an otherwise dark dramatic series,[34] Kevin Dobson as Kojak's trusted young partner, Det. Bobby Crocker, whose on-screen chemistry with Savalas was a success story of 1970s television,[35] and Dan Frazer as Captain Frank McNeil.[36]

Due to a decline in ratings, the series was cancelled by CBS in 1978. Savalas and Frazer were the only actors to appear in all 118 episodes. Savalas was unhappy about the show's demise[37] but got the chance to reprise the Kojak persona in several television movies, starting in 1985.[38][39] The first film, subtitled The Belarus File and broadcast in February 1985, reunited Savalas with several of his co-stars from the series: younger brother George, Dan Frazer, Mark Russell (Det. Saperstein) and Vince Conti (Det. Rizzo); this marked those actors' final appearances in the Kojak franchise.[40][41]

A further six Kojak TV movies were produced, titled The Price of Justice (1987),[42] Ariana, Fatal Flaw (both 1989), Flowers for Matty, It's Always Something—with Kevin Dobson reprising his role of Bobby Crocker, now an assistant district attorney—and None So Blind (all 1990).[43][44]

Later work

[edit]Savalas wrote, directed, and starred in the 1977 independent thriller Beyond Reason, but the film was not released in cinemas; it was made available only on home media in 1985.[45] Savalas was part of an all-star cast in the movies Escape to Athena, Beyond the Poseidon Adventure (both 1979), and Cannonball Run II (1984), and continued to appear in a number of film and television guest roles during the 1980s, including Border Cop (1980) and Faceless (1988), the series Tales of the Unexpected (1981), and two episodes each of The Love Boat (1985) and The Equalizer (1987); the latter series was produced by James McAdams, who had also produced Kojak.

Savalas was the lead actor in the TV movie Hellinger's Law (1981), which was originally planned as a pilot for a series, but ultimately never materialized.[46]

In 1992, he appeared in three episodes of the TV series The Commish (his son-in-law was one of the producers). This was Savalas' final television role. He appeared in two further feature films before his death, Mind Twister (1993) and the posthumous release Backfire! (1995).[28]

Other achievements

[edit]With the $1,000,000 he was paid for On Her Majesty's Secret Service in 1969, Savalas bought The Bridge House, in Ferndown, Dorset, England. A couple of relatives ran it for him as a hotel.

As a singer, Savalas had some chart success. His spoken word version of Bread's "If", produced by Snuff Garrett, reached number one in both the UK and Ireland in March 1975, but just number 88 in Canada,[47] and his follow-up, a version of "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" peaked at No. 47 in the UK.[48] In February 1981, his version of Don Williams' "Some Broken Hearts Never Mend" topped the charts in Switzerland.[49] He worked with composer and producer John Cacavas on many albums,[50] including Telly (1974) (which peaked at No. 12 in the UK[51] and No. 49 in Australia)[52] and Who Loves Ya, Baby (1976).

In the late 1970s, Savalas narrated three UK travelogues titled Telly Savalas Looks at Portsmouth, Telly Savalas Looks at Aberdeen, and Telly Savalas Looks at Birmingham. They were produced by Harold Baim and were examples of quota quickies, which were then part of a requirement that cinemas in the United Kingdom show a set percentage of British-produced films.[53] In the 1980s and early 1990s, Savalas appeared in commercials for the Players' Club Gold Card. In 1982, along with Bob Hope and Linda Evans, he participated in the "world premiere" television ad introducing Diet Coke to Americans.[54] On October 28, 1987, Savalas hosted Return to the Titanic Live, a two-hour television special broadcast from Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie in Paris, which was widely criticized as being insensitive and for making light of the tragic sinking soon after its wreck was discovered.[55][56] He also hosted the 1989 video UFOs and Channeling.

He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1983. In 1999, TV Guide ranked him number 18 on its 50 Greatest TV Stars of All Time list.[57]

Personal life

[edit]

Savalas was married three times. In 1948, after his father's death from bladder cancer, Savalas married his college sweetheart, Katherine Nicolaides. Their daughter Christina, named after his mother, was born in 1950. In 1957, Katherine filed for divorce. She urged him to move back to his mother's house during that same year. While Savalas was going broke, he founded the Garden City Theater Center in his native Garden City. While working there, he met Marilyn Gardner, a theater teacher. They married in 1960. Marilyn gave birth to their daughter, Penelope, in 1961. A second daughter, Candace, was born in 1963. They divorced in 1974, after a long separation.[14]

In January 1969, while working on the movie On Her Majesty's Secret Service, Savalas met Sally Adams (billed as Dani Sheridan, one of Blofeld's "Angels of Death"), an actress 24 years his junior, whose daughter from a previous relationship is Nicollette Sheridan. Savalas later moved in with Sally, who gave birth to their son Nicholas Savalas on February 24, 1973. Although Savalas and Sally Adams never legally married, she went by the name Sally Savalas.[58] They stopped living together in December 1978; she filed a palimony lawsuit against him in 1980, demanding support not only for herself and their son, but also for Nicollette.[58]

In 1977, during the last season of Kojak, Savalas met Julie Hovland, a travel agent from Minnesota. They were married from 1984 until his death and had two children: Christian, an entrepreneur, singer, and songwriter, and Ariana, an actress and singer/songwriter.[59][60] Savalas was close friends with actor John Aniston,[18] and was godfather to his daughter Jennifer, a successful TV and film actress.[61]

Savalas held a degree in psychology and was a world-class poker player who finished 21st at the main event in the 1992 World Series of Poker. He was also a motorcycle racer and lifeguard. His other hobbies and interests included golfing, swimming, reading romantic books, watching football, traveling, collecting luxury cars and gambling. He loved horse racing and bought a racehorse with film director and producer Howard W. Koch. Naming the horse Telly's Pop, it won several races in 1975, including the Norfolk Stakes and Del Mar Futurity.[62][63]

In his capacity as producer for Kojak, he gave many stars their first break, as Burt Lancaster had done for him. He was considered by those who knew him to be a generous, graceful, compassionate man.[citation needed] He was also a strong contributor to his Greek Orthodox roots through the Saint Sophia and Saint Nicholas cathedrals in Los Angeles and was the sponsor of bringing electricity in the 1970s to his ancestral home, Ierakas.

Savalas had a minor physical handicap in that his left index finger was deformed.[64] This deformed digit was often indicated on screen; the Kojak episode "Conspiracy of Fear" in which a close-up of Savalas holding his chin in his hand clearly shows the permanently bent finger.

As a philanthropist and philhellene, Savalas supported many Hellenic causes and made friends in major cities around the world. In Chicago, he often met with Illinois state senators Steven G. Nash and Samuel C. Maragos.

In 1993, Savalas appeared on an Australian TV show, The Extraordinary, with a paranormal tale about a hitchhiking mystery that he could not explain.[65][66]

Along with his brother, Savalas was a Freemason.[67]

In the 1980s, Savalas began to lose close relatives. His brother George Savalas, who played Stavros in the original series, died in 1985 of leukemia at age 60. His mother died in 1988. In late 1989, Savalas was diagnosed with transitional-cell cancer of the bladder.[59][60][68]

Death

[edit]Savalas died on January 22, 1994, of complications of prostate and bladder cancer at the Sheraton-Universal Hotel in Universal City, California, at the age of 72.[68][69][70] He had lived at the Sheraton in Universal City for 20 years, becoming such a fixture at the hotel bar that it was renamed Telly's.[71]

Savalas was interred at the George Washington section of Forest Lawn, Hollywood Hills Cemetery in Los Angeles, California. The funeral, held in the Saint Sophia Greek Orthodox Church, was attended by his third wife, Julie, and his brother Gus. His first two wives, Katherine and Marilyn, also attended with their own children. The mourners included Angie Dickinson, Jennifer Aniston, Kevin Sorbo, Frank Sinatra, Don Rickles, and several of Savalas's Kojak co-stars including Kevin Dobson and Dan Frazer.[72]

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Mad Dog Coll | Lieutenant Darro | |

| The Young Savages | Lieutenant Gunderson | ||

| The Sin of Jesus | Felix | Short subject | |

| 1962 | Cape Fear | Private Detective Charles Sievers | |

| Birdman of Alcatraz | Feto Gomez | Nominated—Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor Nominated—Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | |

| The Interns | Dr. Dominic Riccio | ||

| 1963 | The Man from the Diners' Club | 'Foots' Pulardos | |

| Love Is a Ball | Dr. Christian Gump (Millie's uncle) | ||

| Johnny Cool | Vincenzo 'Vince' Santangelo | ||

| 1964 | The New Interns | Dr. Dominick 'Dom' Riccio | |

| 1965 | The Greatest Story Ever Told | Pontius Pilate | |

| John Goldfarb, Please Come Home! | Macmuid (Harem Recruiter) | Uncredited | |

| Genghis Khan | Shan | ||

| Battle of the Bulge | Sergeant Guffy | Nominated—Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | |

| The Slender Thread | Dr. Joe Coburn | ||

| 1966 | Beau Geste | Sergeant Major Dagineau | |

| 1967 | The Dirty Dozen | Archer Maggott | |

| 1968 | Sol Madrid | Emil Dietrich | |

| The Scalphunters | Jim Howie | ||

| Buona Sera, Mrs. Campbell | Walter Braddock | ||

| 1969 | The Assassination Bureau | Lord Bostwick | |

| Mackenna's Gold | Sergeant Tibbs | ||

| Sophie's Place | Herbie Haseler | Known as Crooks and Coronets in the United Kingdom | |

| On Her Majesty's Secret Service | Ernst Stavro Blofeld | ||

| 1970 | Land Raiders | Vicente Cardenas | |

| Kelly's Heroes | Joe 'Big Joe' | ||

| Violent City | Al Weber | ||

| 1971 | Pretty Maids All in a Row | Surcher | |

| A Town Called Bastard | Don Carlos | ||

| Clay Pigeon | Redford | ||

| 1972 | Crime Boss | Don Vincenzo | |

| Sonny and Jed | Sheriff Franciscus | ||

| Horror Express | Captain Kazan | ||

| The Killer Is on the Phone | Ranko Drasovic | ||

| Pancho Villa | Pancho Villa | ||

| A Reason to Live, a Reason to Die | Maggiore Ward | ||

| 1973 | Senza Ragione | 'Memphis' | |

| 1974 | Lisa and the Devil | Leandro | |

| 1975 | Inside Out | Harry Morgan | |

| 1976 | Killer Force | Harry Webb | |

| 1978 | Capricorn One | Albain | |

| 1979 | Escape to Athena | Zeno | |

| Beyond the Poseidon Adventure | Captain Stefan Svevo | ||

| The Muppet Movie | El Sleezo Tough | ||

| 1980 | Border Cop | Frank Cooper | |

| 1981 | Maria Tomba Homem | Unknown | Mazzaropi, had as objective, to make the next film, with the actor, perhaps with the title KOJECA (parody of the name of the series Kojak), but unfortunately he died before even starting the pre-production of the film, on June 13, 1981. |

| 1982 | Fake-Out | Lieutenant Thurston | |

| 1983 | Afghanistan pourquoi? | Rebel Leader | |

| 1984 | Cannonball Run II | Hymie Kaplan | |

| 1985 | Beyond Reason | Dr. Nicholas Mati | Originally filmed in 1977 and not released theatrically; made available on home video eight years later Also director and writer |

| 1986 | GoBots: Battle of the Rock Lords | Magmar | Voice |

| 1988 | Faceless | Terry Hallen | |

| 1993 | Mind Twister | Richard Howland | |

| 1995 | Backfire! | Most Evil Man | Posthumous release (final film role) |

Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | NBC Sunday Showcase | Cotton | Episode: "Murder and the Android" |

| 1959–1960 | Armstrong Circle Theatre | Dieter Wislieny / Dieter Wisliceny / Father Dominique Georges Henn Pire / Charles Rogan | 6 episodes |

| 1960 | Diagnosis: Unknown | Tony 'Irish Tony' Salivarro | Episode: "Gina, Gina" |

| Dow Hour of Great Mysteries | Unknown | Episode: "The Cat and the Canary" | |

| The Witness | Al Capone / Charlie 'Lucky' Luciano | 3 episodes | |

| Naked City | Gabriel Hody | Episode: "To Walk in Silence" | |

| The United States Steel Hour | Unknown | Episode: "Operation North Star" | |

| 1961 | The Aquanauts | Paul Price | Episode: "Stormy Weather" |

| Acapulco | Mr. Carver | 8 episodes | |

| King of Diamonds | Massis / Jerry Larch | 2 episodes | |

| The New Breed | Dr. Buel Reed | Episode: "The Compulsion to Confess" | |

| The Dick Powell Show | Sergeant Marius | Episode: "Three Soldiers" | |

| The Detectives | Ben | Episode: "Escort" | |

| Ben Casey | George Dempsey | Episode: "A Dark Night for Billy Harris" | |

| 1961–1962 | Cain's Hundred | Harry Remick / Frank Meehan | 2 episodes |

| 1961–1963 | The Untouchables | Leo Stazak / Matt Bass / Wally Baltzer | 3 episodes |

| 1962 | Alcoa Premiere | Mario Lombardi | Episode: "The Hands of Danofrio" |

| 1963 | The Eleventh Hour | Ben Cohen | Episode: "A Tumble from a High White House" |

| The Dakotas | Jake Volet | Episode: "Reformation at Big Nose Butte" | |

| Big G | Tibor | Episode: "Arrow in the Sky" | |

| Grindl | Mr. Hartman | Episode: "The Gruesome Basement" | |

| 77 Sunset Strip | Brother Hendricksen | Episode: "5: Part 4" | |

| The Twilight Zone | Erich Streator | Episode: "Living Doll" | |

| 1963–1965 | Burke's Law | Balakirov, Richard Goldtooth / Charlie Prince / Fakir George O'Shea | 3 episodes |

| 1964 | Kraft Suspense Theatre | Ramon Castillo / Raymond Castle / Beret | 2 episodes |

| Channing | Paul Atherton | Episode: "A Claim to Immortality" | |

| Arrest and Trial | Frank Santo | Episode: "The Revenge of the Worm" | |

| Alfred Hitchcock Presents | Harry 'Philadelphia Harry' | Episode: "A Matter of Murder" | |

| Breaking Point | Vincenzo Gracchi | Episode: "My Hands Are Clean" | |

| The Rogues | General Hector Jesus Diaz | Episode: "Viva Diaz!" | |

| Fanfare for a Death Scene | Ikhedai Khan | Television film | |

| 1964–1966 | The Fugitive | Steve Keller / Victor Leonetti / Dan Polichek | 3 episodes |

| 1964–1967 | Combat! | Jon / Colonel Kapsalis | 2 episodes |

| 1965 | Bonanza | Charles Augustus Hackett | Episode: "To Own the World" |

| Run for Your Life | Istvan Zabor | Episode: "How to Sell Your Soul for Fun and Profit" | |

| 1966 | The Virginian | 'Colonel' Bliss | Episode: "Men with Guns" |

| 1967 | The F.B.I. | Ed Clementi | Episode-2 part: "The Executioners" |

| The Man from U.N.C.L.E | Count Valerino De Fanzini | 2 episodes | |

| Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre | Mueller | Episode: "Don't Wait for Tomorrow" | |

| Garrison's Gorillas | Wheeler | Episode: "The Big Con" | |

| Cimarron Strip | 'Bear' | Episode: "The Battleground" | |

| 1970 | The Red Skelton Show | 'Tex' | Episode: "Stagecoach Hijack" |

| 1971 | ITV Sunday Night Theatre | Gregor Antonescu | Episode: "Man and Boy" |

| Mongo's Back in Town | Lieutenant Pete Tolstad | Television film (also known as Steel Wreath) | |

| 1972 | Visions... | Lieutenant Phil Keegan | Television film |

| 1973 | The Marcus-Nelson Murders | Lieutenant Theo Kojak | Television film Nominated—Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role |

| She Cried Murder | Inspector Joe Brody | Television film | |

| 1973–1978 | Kojak | Lieutenant Theo Kojak | 118 episodes Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Television Series – Drama (1975–1976) Primetime Emmy Award for Best Lead Actor in a Drama Series (1974) Nominated—Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Television Series – Drama (1977–1978) Nominated—Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series (1975) Nominated—Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing in a Drama Series (1975) |

| 1974 | The Carol Burnett Show | Himself | Season 8 Episode 5 |

| 1975 | Am Iaufenden Band | Singer / Kojak | Episode: #2.1 |

| Royal Variety Performance | Himself | Performed in front of Queen Elizabeth II & the Duke of Edinburgh at the London Palladium on November 10, 1975.[73][74] | |

| 1978 | Windows, Doors & Keyholes | Unknown | Television film |

| 1979 | Alice | Himself | Episode: "Has Anyone Here Seen Telly?" |

| The French Atlantic Affair | Father Craig Dunleavy | Television miniseries | |

| 1980 | Alcatraz: The Whole Shocking Story | Cretzer | Television film |

| 1981 | Hellinger's Law | Nick Hellinger | Television film (originally planned as a pilot for a series) |

| Tales of the Unexpected | Joe Brisson | Episode: "Completely Foolproof" | |

| 1982 | American Playhouse | Peter Panakos | Episode: "My Palikari" |

| 1984 | The Cartier Affair | Phil Drexler | Television film |

| 1985 | The Love Boat | Dr. Fabian Cain | 2 episodes |

| Kojak: The Belarus File | Lieutenant Theo Kojak | Television film (featuring returning Kojak co-stars George Savalas, Dan Frazer, Mark Russell and Vince Conti) | |

| George Burns Comedy Week | Unknown | Episode: "The Assignment" | |

| Alice in Wonderland | The Cheshire Cat | Television film | |

| Solomon's Universe | Solomon Stark | ||

| 1987 | Kojak: The Price of Justice | Inspector Theo Kojak | |

| The Dirty Dozen: The Deadly Mission | Major Wright | ||

| The Equalizer | Brother Joseph Heiden | 2 episodes | |

| J.J. Starbuck | The Greek | Episode: "Gold from the Rainbow" | |

| 1988 | The Dirty Dozen: The Fatal Mission | Major Wright | Television film |

| 1989 | The Hollywood Detective | Harry Bell | |

| Kojak: Ariana | Inspector Theo Kojak | ||

| Kojak: Fatal Flaw | |||

| 1990 | Kojak: Flowers for Matty | ||

| Kojak: It's Always Something | Television film (with Kojak co-star Kevin Dobson) | ||

| Kojak: None So Blind | Television film | ||

| 1991 | Rose Against the Odds | George Parnassus | |

| 1991–1993 | Ein Schloß am Wörthersee | Teddy | 2 episodes |

| 1992–1993 | The Commish | Tommy Colette | 3 episodes |

| 1993 | The Extraordinary | Himself | Season 1, Episode 1 |

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Year | Award | Category | Nominated work | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Academy Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Birdman of Alcatraz | Nominated | [75] |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Nominated | [76] | ||

| 1965 | Battle of the Bulge | Nominated | |||

| 1974 | Best Actor in a Television Series – Drama | Kojak | Won | ||

| 1975 | Won[a] | ||||

| 1976 | Nominated | ||||

| 1977 | Nominated | ||||

| 1973 | Primetime Emmy Awards | Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role | The Marcus-Nelson Murders | Nominated | [77] |

| 1974 | Best Lead Actor in a Drama Series | Kojak (Episode: "Requiem for a Cop") | Won | ||

| 1975 | Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series | Kojak | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Directing in a Drama Series | Kojak (Episode: "I Want to Report a Dream...") | Nominated |

Discography

[edit]Albums

[edit]- This is Telly Savalas... (1972)

- Telly (1974)

- Telly Savalas (1975)

- Who Loves Ya Baby (1976)

- Sweet Surprise [released on cassette and CD under the title Some Broken Hearts] (1980)

Singles

[edit]- "Try to Remember" (1972)

- "Look Around You" (1972)

- "I Don't Want To Know / I Walk The Line" (1972)

- "We All End Up The Same" (1972)

- "If" (1974)

- "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' / Help Me Make It Through the Night" (1974)

- "Who Loves Ya Baby" (1975)

- "A Good Time Man Like Me Ain't Got No Business Singing The Blues" (1976)

- "Sweet Surprise" (1980)

- "Some Broken Hearts Never Mend" (1980)

- "Lovin' Understandin' Man" (1981)

- "Goodbye Madame" (1982)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Tied with Robert Blake for Baretta.

References

[edit]- ^ Pompilio, Natalie (October 8, 2015). "Telly Savalas, Who Loves Ya, Baby?". Legacy.com. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "An Evening with Telly Savalas". Cosmos Philly. August 20, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "On this day in 1994, Telly Savalas passes away". Greek City Times. January 21, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Kojak: Telly Savalas". woodmereartmuseum.org. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Garrett, Jamie (March 9, 2015). "What the What? Telly Savalas Had a #1 Hit Song on This Date in 1975". K1017FM.com. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Richardson, Lisa (January 23, 1994). "From the Archives: 'Kojak' Star Telly Savalas Dies at 70". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Telly Savalas Biography (1924–1994)". The Biography Channel. A+E Television Networks, LLC. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ^ "Savalas To Receive Award In '34". Deseret News. July 18, 1991. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Hyland, Wende; Haynes, Roberta (1975). How to make it in Hollywood. Nelson-Hall. p. 135. ISBN 9780882292397.

- ^ Pilato, Herbie J. (2016). Dashing, Daring, and Debonair: TV's Top Male Icons from the 50s, 60s, and 70s. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-63076-052-6.

- ^ "Savalas, Telly A, Cpl". www.army.togetherweserved.com. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "Biography", Telly Savalas official website Archived September 28, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Columbia School of General Studies – Notable Alumni". Columbia University. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Hernandez, Raymond (January 23, 1994). "Telly Savalas, Actor, Dies at 70; Played 'Kojak' in 70's TV Series". The New York Times. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Greeks Around the World. Apopsē Cultural Centre. 1999. p. 178. ISBN 9789608513938.

- ^ "Face Of The Day: Telly Savalas; Still suckers for a seventies cop". The Herald. July 18, 2001. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Pilato 2016, p. 205.

- ^ a b "9 things you never knew about Telly Savalas and Kojak". MeTV. January 21, 2016. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Wolters, Larry (October 30, 1960). "Circle Theater Looks, Decides Not to Leap". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. nwE.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (August 30, 1961). "O'Neill Play Takes Long Night Journey: Iceman Cometh in Own Good Time, but Has Plenty to Say". Los Angeles Times. p. 25.

- ^ Smith, Cecil (September 29, 1960). "THE TV SCENE---: All World Gets Red's Message". Los Angeles Times. p. A13.

- ^ Adams, Val (November 27, 1960). "News Of TV And Radio: Kovacs To Satirize Private Eye ski in a Max Liebman Production -- Items". The New York Times. p. X13.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Telly Savalas". TVGuide.com. TV Guide. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Meyer, Janet L. (2015). Sydney Pollack: A Critical Filmography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7864-3752-8.

- ^ Alpert, Don (August 19, 1962). "Savalas Savvies Tragedy of Success: Telly Savalas". Los Angeles Times. p. N5.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (October 23, 1962). "Eiko Taki, Laurel Goodwin New Finds: They Have It or They Don't; Pre-Sell Buildups Too Costly". Los Angeles Times. p. C9.

- ^ Petersen, Clarence (June 18, 1973). "Telly Savalas turns joke into stardom". Chicago Tribune. p. b16.

- ^ a b King, Susan (February 21, 1993). "Retro Seriously, He'd Rather Go for Laughs". Los Angeles Times (Home ed.). p. 15.

- ^ Page, Don (September 27, 1967). "Telly Savalas—an Actor by Instinct". Los Angeles Times. p. d18.

- ^ a b Shipman, David (January 25, 1994). "Obituary: Telly Savalas". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Adler, Dick (January 20, 1974). "Telly Savalas: he's a latecomer who's made every role count". Los Angeles Times. p. k2.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (August 4, 1996). "Thomas J. Cavanagh Jr., 82, Who Inspired 'Kojak,' Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Clive James. Visions Before Midnight. ISBN 0-330-26464-8.

- ^ Beck, Marilyn (December 14, 1975). "Telly Savalas's mother is not impressed!". Chicago Tribune. p. h7.

- ^ Chapin, Dwight (April 14, 1976). "Kojak Has A Horse That Has Never Been Caught: ... 'Four horses just finished in front of him this time,' Telly Savalas says. His confidence in Telly's Pop is unshaken. Incomplete Source". Los Angeles Times. p. oc_b1.

- ^ Vitello, Paul (December 19, 2011). "Dan Frazer, Fretful Supervisor on 'Kojak,' Dies at 90". The New York Times. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Beck, Marilyn (October 10, 1978). "Telly Savalas works for return of 'Kojak'". Chicago Tribune. p. a8.

- ^ Hill, Michael E. (February 10, 1985). "Telly Savalas: /Kojak Is Back Telly Savalas". The Washington Post. p. 3.

- ^ "Friends remember Kojak star: Cancer claims Savalas, 70". The Windsor Star (FINAL ed.). January 24, 1994. p. B6.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth R. (February 16, 2016). "After Seeing 'Belarus File,' Who'd Love Ya, Kojak?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Jarvis, Jeff (February 18, 1985). "Picks and Pans Review: Kojak: The Belarus File". People. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Kitman, Marvin (February 20, 1987). "The Marvin Kitman Show The New-Old Telly's Back, Baby: [All Editions]". Newsday. p. 05.

- ^ "Kojak". The Official Website of Telly Savalas. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "'Kojak' Is Back With A Few New Wrinkles". Orlando Sentinel. October 24, 1989. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Lee, Grant (June 1, 1977). "FILM CLIPS: Telly Savalas Tackles the Devil". Los Angeles Times. p. f6.

- ^ Beck, Marilyn (March 6, 1980). "Telly Savalas' new show stalls". Chicago Tribune. p. a11.

- ^ "RPM Top 100 Singles - December 14, 1974" (PDF).

- ^ "YOU'VE LOST THAT LOVIN' FEELIN'". Official Charts. May 31, 1975.

- ^ "Discographie Telly Savalas - hitparade.ch". Swisscharts.com.

- ^ Gallo, Phil (January 31, 2014). "John Cacavas, Composer for 'Kojak' and 'Hawaii Five-O,' Dead at 83". Billboard. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "TELLY". Official Charts. March 22, 1975.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 265. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Kojak's kinda town". BBC. April 29, 2008. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ "Insights". Archived from the original on April 11, 2013.

- ^ Corry, John (October 29, 1987). "TV Review; Safe From Titanic Is Opened". The New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ Ringle, Ken (October 29, 1987). "'Titanic ... Live' A Night to Forget". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ TV Guide Guide to TV. Barnes and Noble. 2004. p. 596. ISBN 0-7607-5634-1.

- ^ a b "Telly Savalas slapped with Palimony Suit". BendBulletin.com. The Bulletin. United Press International. November 29, 1980.

- ^ a b Levitt, Shelley (February 7, 1994). "A Thirst for Life". People. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Selim, Jocelyn (August 5, 2013). "Who Loves Ya, Baby?". Cancer Today. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "Jennifer Aniston turns 49 today". Greek City Times. February 11, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "People, Feb. 23, 1976". TIME. February 23, 1976. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ "Owner Koch dead at 84". Thoroughbred Times. February 17, 2001. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ Who2: Celebs Missing Fingers, accessed January 15, 2010

- ^ Telly Savalas' Ghost Story. July 25, 2013. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "I'll Give You a Ride - Remembering "The Extraordinary"". Girl Clumsy. July 13, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ MacKeen, Jason (May 16, 2022). "Famous Freemason - Aristotelis Savalas". Fellowship Lodge. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Telly Savalas". Autopsy: The Last Hours of... (television). Season 13. Episode 4. May 14, 2022.

- ^ Henkel, John (December 1994). "Prostate Cancer: New Tests Create Treatment Dilemmas". FDA Consumer. BNET. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ "Sheraton Universal Hotel". seeing-stars.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2010. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Wharton, David (January 25, 1994). "Telly's Favorite Hotel Knew Him as a Regular Guy". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Pappas, Gregory (January 21, 2018). "Nine Facts You May Not Know About the Late Telly Savalas". The Pappas Post. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "Performances :: 1975, London Palladium | Royal Variety Charity". www.royalvarietycharity.org. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "The Royal Variety Performance 1975". YouTube. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "The 35th Academy Awards (1963) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Telly Savalas". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ "Telly Savalas". Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Telly Savalas at IMDb

- Telly Savalas at the TCM Movie Database

- Telly Savalas discography at Discogs

- Telly Savalas on Find a Grave

- 1922 births

- 1994 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singers

- American Freemasons

- American male film actors

- American people of Greek descent

- American poker players

- American radio personalities

- American male stage actors

- American male television actors

- American television directors

- American television personalities

- Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (television) winners

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)

- Columbia University School of General Studies alumni

- Combat medics

- Deaths from bladder cancer in California

- Deaths from prostate cancer in California

- Kojak

- Male Spaghetti Western actors

- MCA Records artists

- Military personnel from New York (state)

- Outstanding Performance by a Lead Actor in a Drama Series Primetime Emmy Award winners

- People from Floral Park, New York

- People from Garden City, New York

- United States Army non-commissioned officers

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- 20th-century Greek Americans